Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) Injury: Symptoms, Causes, Treatment & Recovery

The knee is the body’s largest joint, making it especially vulnerable to injury. LCL injuries are common in athletes and active individuals because knee ligaments are prone to sprains and tears. While strength training and conditioning provide essential support, some ligament injuries remain unavoidable. Proper care and early treatment can prevent long-term damage.

What is the lateral collateral ligament (LCL)?

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are well-known because the ACL is the most frequently injured knee ligament. However, lateral collateral ligament (LCL) sprains and tears occur far less often. Despite being less common, LCL injuries still require attention and proper treatment to prevent long-term complications. Understanding the difference between these two knee injuries can help you make informed decisions about care.

Knee Anatomy

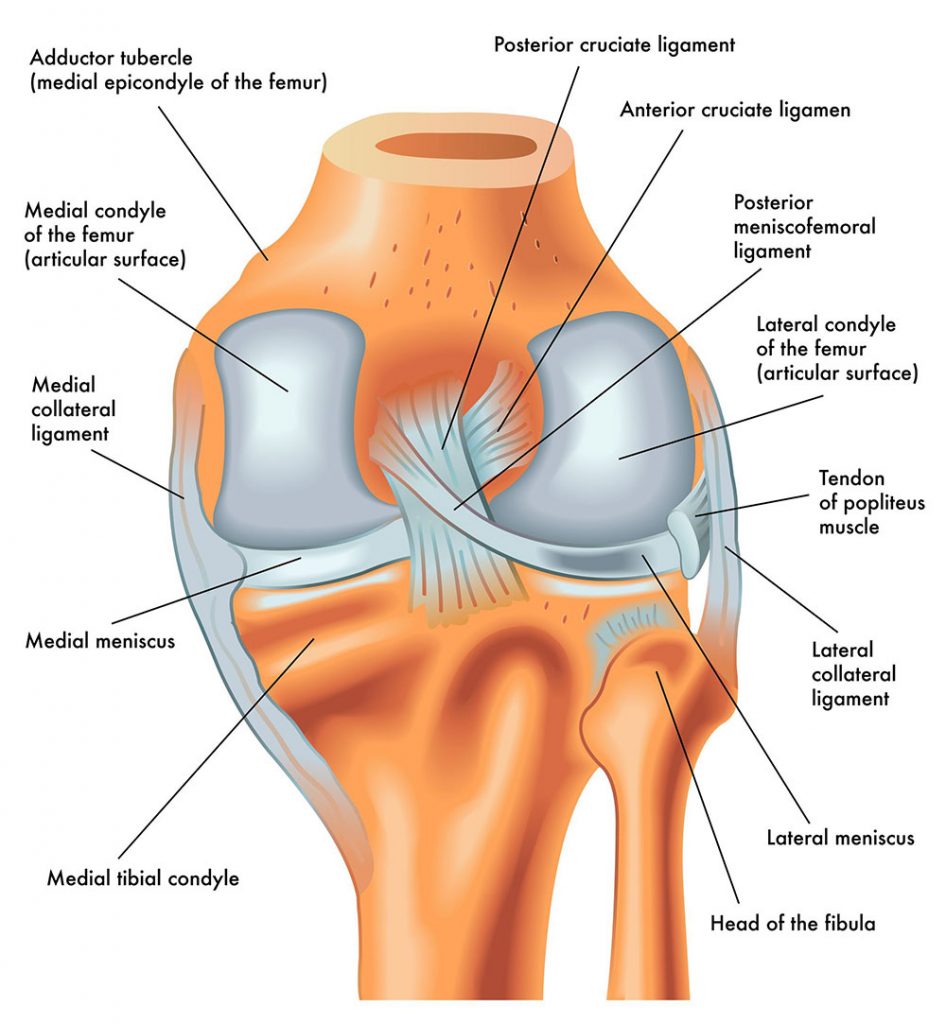

The knee is a complex joint made up of bones, cartilage, tendons and ligaments. Three bones come together to form the knee joint – the femur (thighbone), tibia (shinbone) and patella (kneecap) – and ligaments act as anchors, holding these bones together to keep the knee stable.

There are four main ligaments in the knee that work together to control the back and forth and side-to-side motion of the knee. These ligaments are called cruciate ligaments and collateral ligaments.

Cruciate Ligaments

The knee’s cruciate ligaments – the ACL and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) – cross each other inside the knee, creating an “X” shape of interior support. These ligaments control the back and forth motion of the knee and commonly are injured together.

Collateral Ligaments

The knee’s collateral ligaments – the LCL and the medial collateral ligament (MCL) – are located on either side of the knee and control the sideways motion of the joint, protecting it from unusual movement side-to-side. The MCL runs along the inside of the knee and the LCL runs along the outside of the knee.

Types of LCL Injuries: LCL Sprains and LCL Tears

All ligament injuries fall into three categories: Grade 1 Sprains, Grade 2 Sprains and Grade 3 Sprains. While many people are used to hearing distinctions between ligament sprains and tears, technically all ligament injuries are varying severity of sprains.

Grade 1 LCL Sprain

In a Grade 1 Sprain, the ligament has been stretched and mildly injured but is still able to help keep the knee stable and functional.

Grade 2 LCL Sprain

Often called a partial LCL tear, Grade 2 Sprain occurs when the ligament is stretched or stressed enough to become loose.

Grade 3 LCL Sprain

A Grade 3 Sprain is a complete LCL tear. This means the ligament is torn into two separate pieces and the joint is no longer stable.

Common LCL Injury Causes

The knee’s ligaments and muscles work together to stabilize the joint. However, the knee is highly vulnerable to direct impacts and intense muscle contractions. Quick directional changes, especially while running, often lead to ligament injuries. Athletes commonly suffer from these injuries due to the knee’s constant strain. Although MCL injuries are more frequent, LCL sprains and tears can be just as serious. The outer knee is complex, making LCL injuries more likely to result in additional damage to the joint.

The root cause of LCL injuries is inward stress on the knee, which can cause the LCL ligament on the outside of the knee to stretch, sprain or tear. This inward stress can be caused by traumatic contact or force, jumping, twisting, and quick changes of direction, or from lateral movements that subject the knee to unnatural motion. Football players, soccer players, basketball players and skiers are all prone to LCL injuries.

LCL Injury Symptoms

LCL sprains and tears have similar symptoms that can vary in severity depending on the grade of injury. Symptoms include:

- LCL pain that is mild or acute

- Swelling, tenderness or bruising on the outside of the knee

- A locking or catching in the joint when moved

- Joint stiffness

- A feeling that the knee is unstable or may give out under weight

(Find out when you should see a doctor for knee pain.)

Diagnosis, Treatment and Recovery

Most LCL injuries can be diagnosed with a physical exam by an orthopedic specialist, though MRIs and X-rays can help determine if there is definite ligament damage or broken bones affecting the LCL, respectively.

Surgery on collateral ligaments – LCL and MCL – is not as common as surgeries for ACL and PCL injuries. However, LCL injuries tend to involve other structures in the knee that often require additional treatment. If treated correctly, most LCL sprains will heal

The three main nonsurgical treatments for LCL injuries are ice, bracing and physical therapy. Immediately after injury, ice applied to the injured area for 15 to 20 minutes at a time every hour can help reduce swelling and inflammation of the joint. Bracing the knee to protect the ligament from further sideways movements can also help speed the healing process.

Your orthopedic knee specialist will likely prescribe physical therapy to strengthen the muscles around your knee. Physical therapy targets your specific needs and aids in recovery. During your sessions, your therapist will guide you through exercises that restore mobility and improve function. These exercises also help boost strength and enhance overall knee stability.

If you are suffering from LCL pain or believe you have a ligament injury, please feel free to contact us with any questions or concerns and one of our orthopedic surgeons will do what they can to help.

1 Comment

Permalink

Can LCL injuries need more prone to happen because of tight hamstrings? I notice what I think to be a slight injury in both LCLs at times in my knees in basketball when my foot or leg lands a certain way, and I usually have tighter hamstrings.