PCL and LCL Injuries: Common Causes and Symptoms

Most people are familiar – some intimately – with their knees’ ACLs (anterior cruciate ligaments) and MCLs (medial collateral ligaments). As the two most common ligaments in the knee that are injured every year, the ACL and MCL get a lot of attention. There are, however, two other ligaments that play important roles in the knee joint: the PCL and LCL.

What is the PCL?

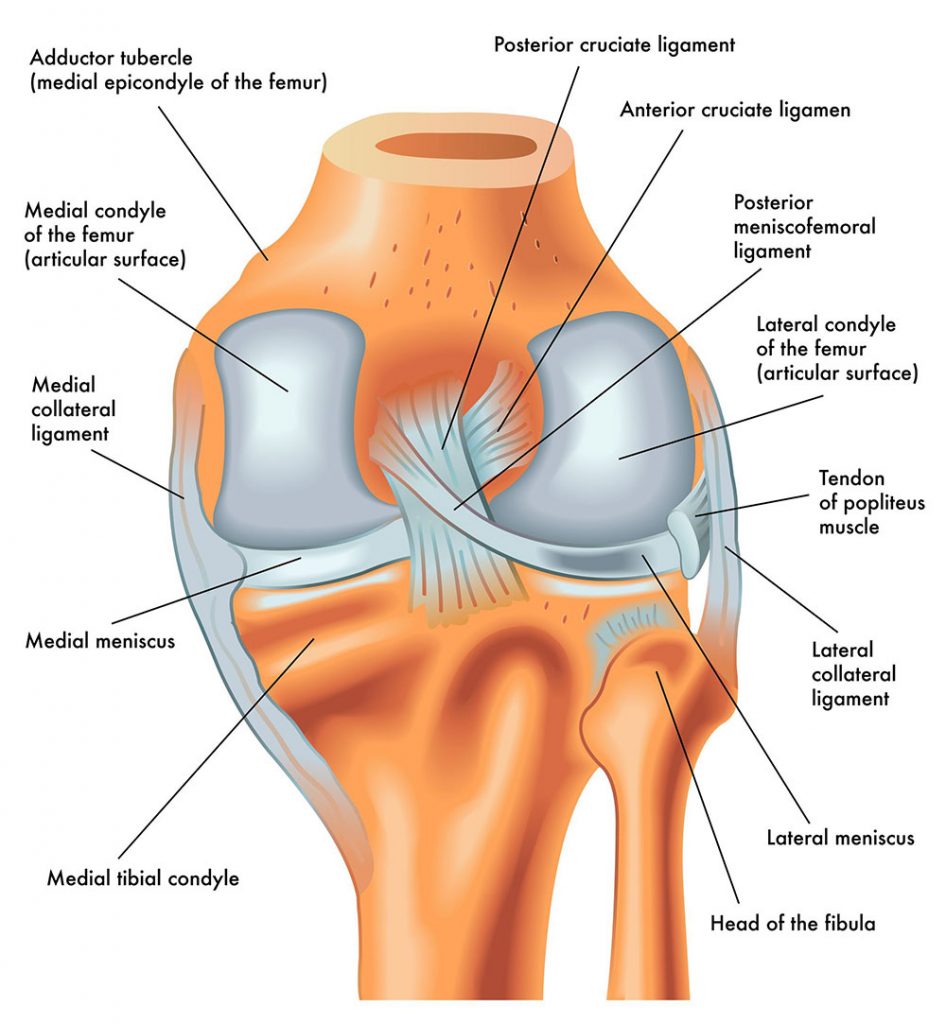

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) partners with the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Both are strong tissue bands connecting the thighbone (femur) to the tibia at the knee joint. They work together to stabilize the knee. Additionally, they protect against front-to-back and back-to-front impacts. This creates an “X” pattern of support across the knee joint.

In this partnership, the PCL plays a crucial role in stabilizing the knee. Specifically, it prevents the lower leg from sliding excessively backward relative to the upper leg. This function is especially important when the knee is bent. By maintaining this stability, the PCL ensures proper alignment and movement, enhancing overall knee function.

What is the LCL?

The MCL and LCL, like the ACL and PCL, are crucial for stabilizing the knee joint. These collateral ligaments are positioned on the knee’s outer sides. Specifically, the LCL is situated on the outer aspect, whereas the MCL is found on the inner side of the joint. Both ligaments are essential for controlling sideways movements of the knee, ensuring its stability and proper function.

PCL Injuries: Sprains and Tears

A PCL injury occurs when the ligament is overly stretched or torn by an unusual movement or force. According to Harvard Health Publishing, the PCL is most commonly injured during automobile accidents and in sports when athletes fall forward on a bent knee.

All ligament injuries are considered “sprains” – even if the ligament is technically torn. As with any other ligament injury, PCL injuries fall into three categories: Grade I Sprains, Grade II Sprains and Grade III Sprains.

Grade I PCL Injury

A Grade I injury involves a mild stretching of the ligament. In many cases, this injury may go unnoticed. Typically, it does not significantly impact knee stability. However, it’s essential to address even minor injuries to prevent further issues.

Grade II PCL Injury

A Grade II injury is classified as moderate. This type of injury occurs when the ligament is either partially torn or excessively stretched, leading to looseness and instability in the knee. Consequently, the knee may buckle or give out during certain activities. Thus, it’s crucial to address Grade II injuries promptly to prevent further complications.

Grade III PCL Injury

A Grade III injury occurs when the PCL is either fully torn or completely detached from one or both of its anchor bones. This serious condition usually results from a substantial impact. Furthermore, such severe trauma often damages other knee structures, including the ACL and MCL.

Types of LCL Sprains

LCL injures are graded on the same three levels as PCL injuries, with small adjustments in terms of pain location and knee function. Also similar to Grade III PCL injuries, Grade III LCL injuries are typically accompanied by tears to the ACL or other knee injuries.

The most common causes of LCL injuries are a direct impact to the inside of the knee, landing awkwardly or poorly from a jump and changing directions quickly.

PCL Knee Injury Symptoms

PCL injuries often have such mild symptoms that a PCL tear may only be discovered while diagnosing another knee injury. Many athletes unknowingly continue to compete after a PCL injury and tend to say that their knee “just doesn’t feel right” once they do seek treatment.

PCL tear symptoms may include:

- Mild pain at the back of the knee that worsens when kneeling

- Mild swelling

- Pain in the front of the knee, particularly while running or slowing down

LCL Kneed Injury Symptoms

If you’ve injured your LCL, you’re most likely experiencing pain and swelling.

Other common LCL tear symptoms include:

- Stiffness, soreness or tenderness on the outside of the knee

- A feeling that your knee may give out while standing or walking

- Your knee catches or locks in place while you walk

- Bruising around the knee

- A reduced range of motion

- Knee pain and foot numbness

If you think you’ve suffered a PCL or LCL injury and would like to consult a knee specialist, please feel free to contact us. Our orthopedic surgeons are happy to answer any questions you may have.

7 Comments

Permalink

Knee injury’s skiing. Unclear if it is pcl or as lcl of left knee. I can still ski with pain. Real pain comes from turning my left ski outwards. I have difficulty with three heel slide exercise. Can’t bring my heel back to buttocks. Also challenges going down steps. That’s why I thought pcl. But, the long the inside of the lcl makes me think otherwise. Oddly enough, I never had any swelling or bruising. Thoughts?

Permalink

Hi Jonathan,

It sounds like you could be dealing with a complex issue involving your knee ligaments. Difficulty with the heel slide exercise and difficulty going down steps could be indicative of a ligament issue, as you mentioned. Given the uncertainty between the PCL and LCL, we recommend seeking an evaluation from an orthopedic specialist. They can conduct a physical examination and may recommend imaging studies, such as an MRI, to get a clearer picture of the injury.

Permalink

I have pain at the back of my knee toward the middle and outside (laterally). The pain is a 1/10 when I am standing or sitting, however, if I were to stretch my quad pulling my heel to my butt, I get to about 4/10. Similar things like crouching down into a sumos quat are very difficult for me at the moment.

Permalink

I am a healthy, fairly actice 54 yoa male who snow skiis, water skiis, mountain bikes, and rides dirt/trail motorcycles.

I recently crashed on my dirt bike causing a complete tear to my MCL and a partial tear to my PCL.

My local Ortho Dr. Stated that I did not need surgery citing my age as one of the factors.

Being unable to afford a second opinion with Xrays and MRIs, I was just curious if this is a normal conclusion or should I get a second opinion.

Permalink

Hi Robert,

It is reasonable to treat these injuries nonoperatively with bracing, rest, anti-inflammatories, and ice. These tears often heal without surgical management. It may take up to 8 weeks to fully return to activities. If you continue to have instability when attempting to return to your active lifestyle, then you may consider re-evaluation of your knee.

Permalink

I have been having ongoing significant pain for the last three weeks or more in my right knee on the inside. At times it feels like somebody is jamming needles into me. I’ve been taking 3 to 4 Aleve at a time and it does not touch the pain. I am 55 and overweight. And my doctor ordered an x-ray and just told me I have arthritis. I know the doll pain of arthritis. I know you scale of 1 to 10 the pain is between seven and nine. Ice seems to intensify the pain. What should I do to alleviate pain

Permalink

Vickie,

If you have been having pain for the last 3-4 weeks then the goal would be to get you back to feeling how you did prior. Since we are not able to look at your radiographs, we cannot confirm if it is indeed osteoarthritis that is causing your pain. A cortisone injection may be an option for you that you could ask your orthopedic surgeon about. If you are feeling symptoms of catching, locking, or your knee giving way then a MRI may be an option to evaluate for a meniscus tear. Hope this helps.